Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericsson opens by dismantling one of the biggest myths floating around in sports, Reddit threads, and everyday conversations. The idea that elite performers are simply “born different.” You know the one: some people just have it, and others don’t.

Ericsson’s research flips that belief completely. He argues that what we call “talent” is usually the visible result of years of purposeful, structured, feedback-driven practice — not some mysterious genetic gift. His work forces you to rethink what separates an expert from everyone else, and whether mastery is something anyone can build with the right process.

When I first read Peak, I was beginning my coaching journey. Starting with boxing, later with esports and CDL teams. This book challenged me on how greatness was actually. The context, the person, the environment. Still, a few of the ideas in this book have become non-negotiables for me. They shaped how I coach, how I practice, and how I think about performance. For you who wants to chase excellence in what you do, this is one of the books for you.

So this isn’t a chapter-by-chapter breakdown of Peak.

It’s a deep dive into the lessons that stuck. The ones that changed how I approached mastery, my mindset to talent and how I help others see it.

If you’re reading this, you probably want to skip the fluff and get straight to what matters. These are the core takeaways that have stood the test of time for me — concepts I’ve lived, tested, and built into my own systems of practice that you can too.

Your Practise Isn’t Purposeful

“Don’t Confuse Repetition With Improvement“

Anders mentions that Purposeful Practice ≠ Naïve Repetition

Just because you grind 10 hours a day on COD, VAL, or football doesn’t mean you’re getting better. Shooting bots for 8 hours isn’t skill-building — it’s comfort-building.

That’s what Anders calls Naïve Practice. Doing the same thing over and over, without feedback, focus, or a goal.

Think about it: how many players do you know who put in as much time as the pros but never seem to reach their level of understanding or performance? I was one of them.

Naïve practice builds comfort.

Purposeful practice builds capability.

Purposeful Practice: What It Actually Means

“Purposeful Practise Builds Capability”

Purposeful practice is training at the edge of your ability — not past it, but right on the line.

It’s deliberate discomfort: controlled, measurable, repeatable discomfort.

It’s about:

- Making adjustments

- Defining a clear outcome

- Testing yourself at the edge of failure

- Seeking feedback (which requires humility)

“You’re not repeating motions — you’re running experiments on your own improvement system.”

Boxing — Turning Practice into Experimentation

When I was coaching and training boxing, my coach Sam used to drill me on distance management through the jab. It wasn’t just about throwing a hundred jabs but, it was about tracking how many landed cleanly depending on how close or far I was from the bag or spar partner.

Once we identified my optimal range (I’m tall, so that mattered), we paired it with footwork drills to move in and out without crossing my legs.

Suddenly, practice wasn’t random. It was targeted.

Every jab became data.

Every rep, feedback.

That’s purposeful practice.

And with that, purposeful practice turned performance into an experiment. I was not repeating motions but running tests on my own improvement system.

You might ask. How does this apply to COD or any other esports?

Applying this to COD and Esports

We implemented this during our 2022 – 2024 seasons, in two ways.

- Through deliberate practise via goal setting

- Through a concept called scripting. (Shoutout OpTic Coach JP sharing this concept already on Social Media.)

“You can deliberately practise, even on a situational game like COD”

I preface this by saying: COD is chaotic — tons of variables, on-the-fly decisions. But not everything is unpredictable. Many situations repeat. That’s where purposeful practice thrives.

Linear Situations

You will have linear situations, and systems that you will often find yourselves in – repeatable. With COD esports, there are only X amount of practical decisions you can make. Practical relating to winning. Sure, you could sit at the back of the map. But, in relation to winning, teamwork or a system, there aren’t as many as you think.

Think about your team going 4 dead. First wave of a hill. Each hill will have an optimal way to play or break based on your spawn. Play that situation enough times, and you can figure out the small % advantages of reducing the disadvantage you’re in. The lanes you want to fill, the positions you want to play, the bait and switching you want to do, the way you want to chall fights. To put it simply, if you are in a disadvantageous position a 100 times, you will end up figuring out what works best. From that foundation, you can add nuance and adapt on the fly.

Now you’re no longer reacting. You’re recognizing structures.

That’s how you move from guessing to anticipating — from playing the game to reading it.

To give you an example, I would use data to figure out what we needed to work on. Patterns would emerge. We would then deliberately and purposefully give teams a rotation, to work on breaking it. Or we would give teams bomb sites, to practise common retakes. You’ll realise, okay, if we tried breaking this hill a 100 times, you will come across a lot of different situational – and with that – decisions you can make.

You’ll come across ways that work, and don’t work. Ways that work because a team did X or Y. Ways that didn’t work because teams did X or Y.

Now you aren’t going to play that situation the exact same way, every single time, you become predictable. What you will do is have a better understanding on how it all works together. That way, you can adapt in the moment and call audibles.

This leads me onto strategic scripting.

Strategic Scripting: How Pros Pre-Think Pressure

Strategic scripting is essentially, if we do X or get X info, we will do Y.

Scripting is crucial from a psychological standpoint. It is the basis of every single sport. We would script in boxing. You do this in COD, without realising. We can be deliberate and purposeful about this.

You might think, well in COD why do we need to script, it’s so different from traditional sports? Well, no it isn’t. Scripting shapes your decision making, self confidence and team cohesion. It’s also the reason why I hate the way SND is practised at the CDL level – but, that’s a different discussion.

Scripting doesn’t kill creativity. It reduces cognitive load under pressure.

That’s why when you see teams choke, or don’t perform as well in scrims. It has little to do with the talent and more the optimisation of performance and pressure. The faster the games, the faster the decision making, the less times players have to think and make A decision – never mind the optimal one. When you pre-decide how you want to react from information, it frees up your mental capacity to focus and execute under pressure IN THE MOMENT. It doesn’t mean you HAVE to follow through, it gives you the foresight to know how you would and if you want to call an audible. I promise you, Grand Finals on a Championship, you’re not going to be thinking as clearly as you could.

This is why preparation for all my teams was crucial, if we knew what you guys were doing, or repeatable tendencies on SND – as an example – we could script. Didn’t mean we would PLAY to COUNTER you – play your game – but, we had a better idea on how we wanted to approach our SND playbook. Team overview, player tendencies, team playbook tracking, sequence logs, counter-prep notes. You name it – all scripted, all adaptive.

It’s not about being robotic. It’s about being ready.

Neurologically, it improves your anticipation and situational awareness as thinking in terms of “if X, then Y,” players train their brains to predict opponents’ actions. Anticipation speeds up reactions, making responses almost automatic in real time.

Scripting can include contingencies too, which helps you adapt during high pressure situations without panicking.

Give it a try the next time you play. If enemies do X, i will do Y. If we do X, i will do Y!

Feedback Loops: The Core of Improvement

“Improvement depends on knowing exactly what you’re doing wrong and how to fix it.“

Without feedback, practise becomes blind repetition. It can come from your coaches or team mates – and most importantly, DATA.

In his research, the difference between high and low performers wasn’t who worked harder — it was who received clearer, faster feedback.

When you receive feedback – i don’t call it criticism anymore, shoutout Fish – you tighten the learning loop. This failure will convert into data.

For example:

- Musicians use recordings to identify inconsistencies in tone.

- Athletes use sensors and slow-motion video to analyze movement patterns.

- In coaching or esports, watching VODs after a match with timestamps on every macro-mistake turns a game into a training session.

The lesson is universal: if your feedback is vague, your progress will be too.

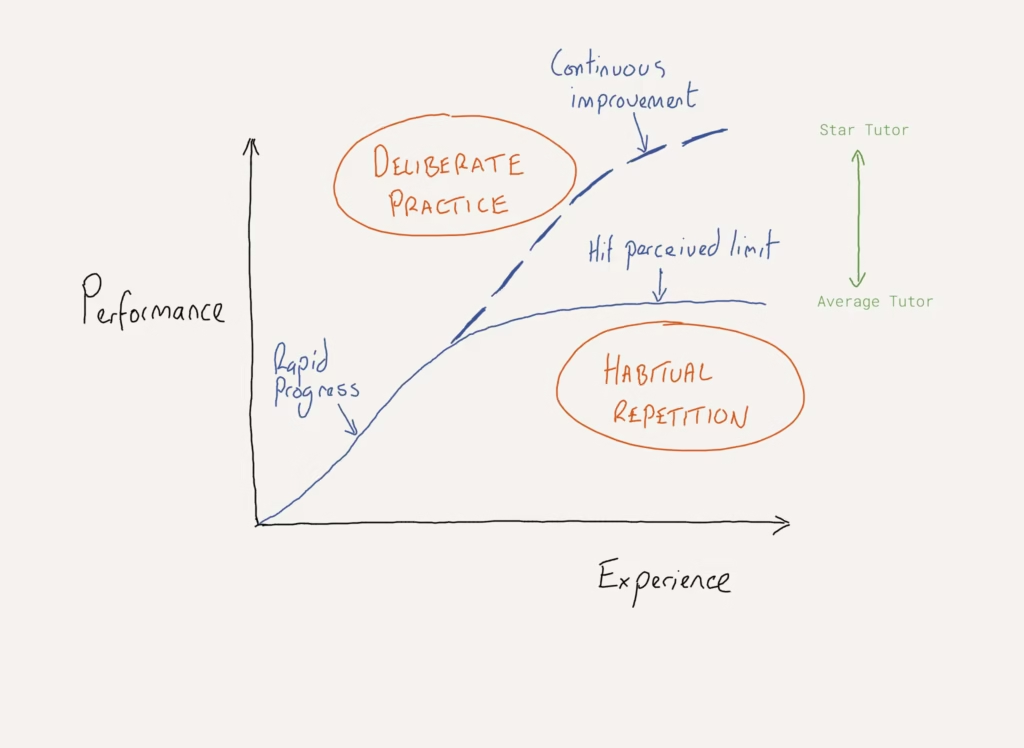

The “OK Plateau”: Why You Stop Improving

“We all plateau when our skills become automatic”

I promise you, this happens to everyone on COD.

This is what we call the OK Plateau.

This is for my crimson and iridescent players who struggle to improve. This is the zone where you’re competent enough but, you don’t feel like you’re improving.

Purposeful practice breaks the plateau. It forces awareness back into the process.

It replaces autopilot with analysis.

Think about how this applies across domains:

- A boxer stops improving when every round feels routine.

- A gamer plateaus when scrims become habitual, not experimental.

- A coach plateaus when they stop reviewing their own systems and feedback methods.

In every field, comfort is the enemy of growth. I’ve written a couple journals about that mindset above, chasing winning and excellence.

The solution? Intentionally design friction into your training. Create drills that stretch specific weak points. Track, review, and refine — relentlessly. For example, change the weapon you use. Use an SMG if you’re an AR. Change what position you play on a bomb site.

If you only play A on Redcard, and you play this 1000 times, you will be pretty competent and understand how to react to most linear situations. But, it doesn’t and won’t give you the entire picture. Now try this on B. Develop that full picture. This is MASTERY. Once you know how teams situations, you anticipate it, steal it, change it, copy it.

That’s the foundation of deliberate practice, which Anders explores in later chapters. But purposeful practice is the spark. It’s the first shift from going through the motions to consciously building excellence.

Reflection Prompts

- When did I last feel genuine challenge in a skill I care about?

(If I can’t remember, I’m probably not practicing — just performing.) - How can I create immediate feedback in my learning process?

(Can I record, measure, or review my performance systematically?) - What does “slightly beyond my current level” look like right now?

(Be specific — what’s the next micro-skill, not the big vague goal?) - When do I tend to slip into autopilot in my training, work, or coaching?

(What triggers complacency — and how can I interrupt it?)

Adaptability – your super-power

“Human ability is not fixed — it’s adaptable..”

Ericsson’s second chapter explores one of the most liberating ideas in performance science:

human ability is not fixed — it’s adaptable.

Our bodies, brains, and even perception systems are plastic, constantly rewiring themselves in response to demand. That adaptability is the real “talent.”

The best COD players in the world, along with their structure and repetition, have this adaptability.

This chapter is where the myth of innate ability finally dies. The message is simple, but it changes everything:

“You can literally become more capable through structured strain.

The human system rewrites itself when challenged deliberately.”

A consistent trait between the athletes I’ve studied and the players I’ve worked with are the growth mindset. There’s a consistent neuroscience and physiological aspect. Every expert performer — musician, athlete, chess player, memory champion — is a living example of the body’s ability to restructure itself around consistent, targeted effort.

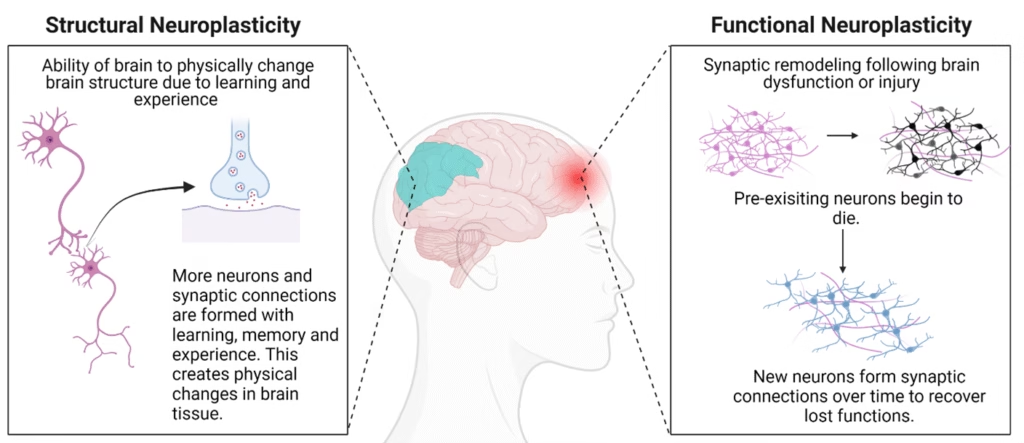

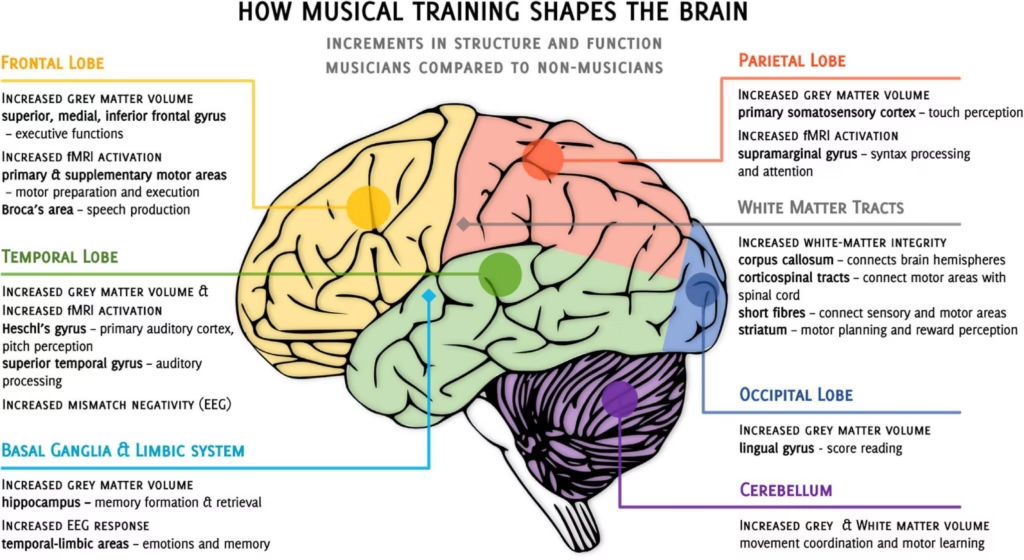

Some of the boring neuroscience behind this: When we practice in a focused, feedback-driven way, our brains and bodies adapt by:

- Creating new neural connections (synaptic growth and myelination)

- Refining motor patterns through repetition and error correction

- Reallocating cortical space to areas of higher demand

That’s why a violinist’s brain literally looks different from a non-musician’s.

It’s why elite athletes have refined neural efficiency in specific motor regions.

Their systems have morphed around the requirements of their practice.

Your brain BECOMES the skill.

So how does it actually work and how can we apply this to our game?

The Cycle: Disruption → Recovery → Growth

Anders describes the adaptation as a cycle. You have Disruption, Recovery and Growth.

Disruption is when you challenge the system. When you push yourself beyond comfort. Think about viewers playing in my viewer 8s even though there are people higher than your rank there. At the discomfort of getting slammed. Think about trying to play the best team on a specific map or mode.

Recovery is when your system recalibrates to handle the new demand. It’s why when people ask how do you improve fast, alongside deliberate practise, you need to keep pushing the bar on who you play. Get involved in them SND 8s, get involved in tournaments. Anything that gets you exposure to be uncomfortable and against the best. It’s my single most biggest regret as a competitor, not seeing out discomfort by getting slammed against the best. It’s why I have so much respect for Doug Censor who did anything he could, including paying his opponents, to get higher skilled practise.

Growth is when what was once difficult becomes routine and automatic. Everything becomes sharper. Decision making, quicker. Processing, faster.

“This process mirrors how muscles grow stronger under resistance.”

In fact, Anders borrows directly from the logic of physical training — progressive overload — and shows that it applies to mental and perceptual skills too. As you need to increase either your reps, time under tension, sets or weight for progressive overload, same thing applies here.

The body and brain crave efficiency. When faced with a new challenge, they adapt by finding faster, smoother, and more precise ways to execute the same task.

That’s what “getting better” really is — internal systems reorganizing to make effort easier and performance sharper.

Adaptation isn’t for everything

“Improvement doesn’t transfer easily between domains.”

Just because you train with a purpose on Halo, doesn’t necessarily mean it will entirely transfer over to COD. I know that’s the hot topic of the month.

Training your memory for numbers won’t improve your memory for names.

Being a fast boxer won’t automatically make you a fast sprinter.

Mastering chess doesn’t make you a better strategist in poker.

Now, there is obviously cross-pollination in skills involved. Absolutely. But each domain builds its own representation system — its own mental architecture for processing information.

Think about basic concepts such as cross hair placement. Your cross hair placement on halo will be natural and automatic but, get to COD, it won’t be as smooth. Not until you practise deliberately, and with a purpose. That’s because the variables that contribute to your automatic cross hair placement on halo, haven’t been established for COD. It is its OWN representation system.

Experts see and interpret their domain differently because their brains have developed specialized filters for recognizing patterns.

- A fighter doesn’t react to punches; he reads intent and rhythm.

- A musician doesn’t read notes; she feels tonal relationships.

- A grandmaster doesn’t “see” chess pieces; he sees strategic structures.

This is why “grinding” random skills won’t make you elite. Improvement happens through specificity — practice that directly mirrors the real performance environment.

“If your training doesn’t look or feel like the environment you want to perform in — your brain won’t adapt correctly.”

As coaches our jobs are to engineer adaptive environments

Coaches in COD.

In my opinion, one of the many roles of a coach, no matter the discipline, is to engineer adaptive environments. This is part of the system you adopt, the philosophy you hold, the tacit experience you possess and the culture you intentionally set.

“The best coaches are the best teachers”

Our responsibility is to:

- Design practice that stretches without overwhelming.

- Create fast feedback loops that turn failure into data.

- Encourage reflection and rest as part of the cycle.

- Build specificity — the closer your practice environment is to the real thing, the more powerful the adaptation.

The measure of a good coach isn’t how hard they push — it’s how intelligently they adapt the system to sustain continuous, focused strain over time.

“The elite don’t practice more. They adapt more efficiently.”

Reflection Prompts

- How can I train adaptability itself — not just skills, but the ability to learn under pressure?

- Where am I currently overreaching (too much stress) or under-challenging (too little stretch)?

- How can I make my practice or coaching environments more specific to real performance conditions?

- Do I treat rest and reflection as part of the training system, or as something extra?

- What am I doing regularly that my brain is adapting to unintentionally (e.g., distraction, multitasking, inconsistent focus)?

Rethink what potential is

What does this mean for how we live, learn, and teach?

I have had this argument on reddit. And it stems from this book.

Anders closes the book by dismantling the last and most dangerous myth.

The idea that human potential is inherently limited.

He shows how this belief quietly shapes how we coach, parent, teach, and even talk to ourselves.

Not only does he claim it’s wrong but, he claims that these are damaging. Because once you see or believe that talent is fixed, or entirely God-given or genetic, then you stop designing systems for growth.

I have SEEN this with multiple players who went from scrub to star.

“The right kind of practice can turn anyone into an expert.

The wrong mindset can stop anyone from trying.”

The Talent Myth

The talent that most of you think of is called innate talent. The talent that you believe is god given or genetic. The talent that defines your ceiling and how successful you can be. The talent that people would claim on COMP COD Reddit that they can’t attain. Especially for esports.

We love the story of the prodigy — the “born genius” who succeeds effortlessly. It makes greatness seem special, magical… and unreachable. You might have a few examples in your head.

But the problem is this:

When we attribute performance to talent, we remove responsibility — from the athlete, from the players, from the coach, from the system.

We stop asking:

- How was that skill built?

- What structure made that improvement possible?

- What feedback loop was in place?

We just say, “They’re gifted,” and move on.

And in doing so, we cut off the possibility of replication.

Anders research — from memory experiments to music academies to sports programs — shows again and again that greatness is not an act of destiny; it’s a by-product of design.

You can change your potential

“Improvement has no clear ceiling“

The biggest revelation in Peak isn’t that people can improve — it’s that improvement has no clear ceiling when practice is properly structured.

This means that your limit isn’t genetical but, rather practical.

Practical meaning this. The time you put in, the resources available, quality of coaching and feedback, your motivation, discipline and drive, and the recovery from it all.

What we usually call “potential” is just the visible result of how well those variables are managed. He says you think of potential as the rate of adaptation over time. Not the measure of talent.

For example:

- A fighter might have “raw power,” but without structure, that potential decays.

- A player might lack early skill, but with disciplined feedback loops, they surpass the “naturally talented” in a few years.

That’s why Anders work redefines what “gifted” really means.

It’s not someone with special genes — it’s someone who, early on, learns how to learn effectively.

That’s the real edge.

The Threshold Between Good and Great

Okay, so all of that so far is good. By why are some people good, and other great? It’s really simple. Almost everyone who learns a skill improves quickly at first, then plateaus.

This is the “automatic phase”. The point where you can perform comfortably, but no longer improve.

In most fields, this is good enough. Teachers, managers, and even athletes often stop here.

But Anders says for the top 1%, that’s where the real work starts.

The elite treat the plateau not as a signal to stop, but as a call to redesign their practice.

They understand that improvement requires constant friction — sustained work at the edge of ability. And that makes sense. Think about my other journals, of Kobe and MJ. Even on COD i’ve seen it with a couple of my elite players. They get to the point where they feel like the plateaued. Then they change a couple things that challenge them to become deliberate.

The shift from purposeful to deliberate practice happens when:

- You have access to a well-developed field where the paths to expertise are already mapped. Think of Crim relying on his decade worth of experience

- You work with a teacher or coach who can precisely diagnose weaknesses. Again, the coach doesn’t NEED to be a PRO but, have sustained experience and knowledge at the highest level. Think of JP.

- You refine your skill through targeted drills that stretch your limits daily.

In other words they stop just “working hard” and start working smart, within a proven structure.

That’s the bridge between good and great.

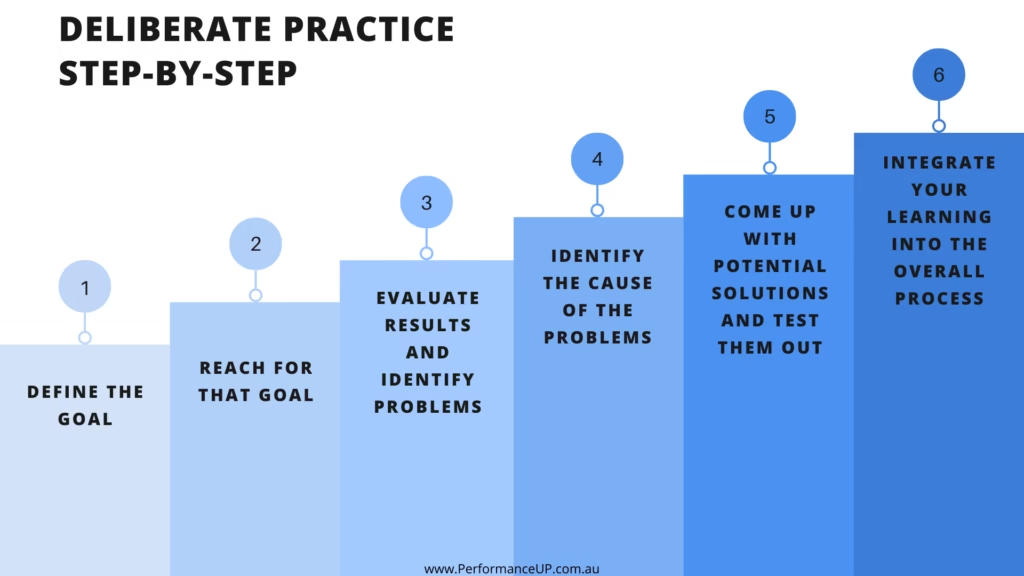

What makes practice deliberate?

He identifies four defining elements that separate deliberate practice from regular training:

- Designed by experts:

The training methods come from the accumulated experience of top performers and teachers. You’re not guessing what to work on — the roadmap already exists – again, having people who’ve actively engaged or learnt from a high performing environments. It’s not good enough to sit and watch the game 14 hours a day on your own. Actively learning, reflecting and engaging with other high level professionals help to refine that. Even if you don’t have that playing ability. Think of the Youtuber vs Kenny argument. Think of JP developing his experience, expertise and tacit experience from active high level play for the past X years. No denying, you can get to a good level from the work you put in but, without that exposure to high performing environments, you will struggle to be great. In my opinion. Myself, I had played to a good level, once I was in that environment consistently, I had picked up a lot of tacit experience and intuition. - Targeted skill refinement:

You’re not practicing “performance” — you’re practicing components of performance.

A violinist isolates finger placement; a boxer isolates head movement; - Immediate, specific feedback:

You know exactly what went wrong, and what to do about it — often within seconds. - Consistent stretch-zone challenge:

Each session pushes slightly beyond your current level — not overwhelming, but never easy.

The real difference is in structure. Deliberate practice is usually not fun it’s cognitively demanding, often frustrating, and mentally exhausting. You CAN have fun doing it but, it’s the kind of work that reshapes your skill from the inside out.

“Deliberate practice is the gold standard for improvement. It’s how all great performers are made.”

Coaching in Esports

“The people who design environments for growth — coaches, teachers, leaders — hold the real power.“

This quote to me explains what coaching should be for COD or any esport. A coach has the real power over an athletes career, or esport players career – if done correctly.

He challenges these roles directly: If expertise is built, not born, then every failure to improve is partly a design problem.

A few questions he suggests we start asking:

Are we teaching how to practice — or just what to do?

Does our practice system provide clear feedback?

Does it target specific weaknesses?

Does it push learners into the stretch zone consistently?

And to me, through the experience over the last few years, and that of Boxing is an issue in esports. Especially from Pro Players who transition over to coaching are at risk of this. Of saying “WHAT” to do rather “HOW” to practise and learn.

That is why the best coaches in sports are also the best teachers. That’s attributes partly to the inconsistency of success for former professionals turned coaches in traditional and esports.

Because when someone fails to progress, it’s rarely because they lack potential — it’s because the system failed to engage their adaptability.

That’s the real revolution Anders was calling for — not just in sports or education, but in how society thinks about learning itself.

As a coach, this hits me directly.

It reframes your job: you’re not there to inspire effort; you’re there to engineer progress. I know of new coaches who come into the league and try to do too much. Try to impress with Xs and Os. But, that doesn’t facilitate learning. Motivation fades, but systems don’t.

And once you build systems that make improvement inevitable, performance becomes a natural consequence.

That’s a reason why culture is difficult to produce in esports. Coaching turnover is incredibly high. You don’t have time during the pressure crunch of a season to establish that. That’s a big reason why it’s difficult to engineer progress that facilitate learning.

Role of Coaches, Teachers and Experts

This is going to be controversial. I know Coaches in COD are seen as hype men. But good coaches are not there to hype you up. You don’t need or should want hype for high performance. Hype ruins focus. Hype introduces emotion to decision making.

Anders emphasizes that deliberate practice requires a guide. No one becomes world-class by trial and error alone — even prodigies rely on structured mentorship.

Our primary role as Coaches should not be for motivation. It isn’t to say the right thing at the right time to motivate someone. Screw your motivation.

A role of a coach is diagnostic. Our jobs are to observe, detect macro and micro-errors, and prescribe drills that target those specific flaws. To Problem solve.

Coaches are high performance mechanics tuning an engine.

The coach identifies inefficiencies you can’t see. They create drills to fix those inefficiencies. You execute those drills deliberately until the weakness becomes a strength.

A coach who can spot invisible patterns (footwork rhythm, timing inconsistencies, mental resets after losses) and turn them into drills is doing true deliberate practice work.

Without that kind of feedback, even the hardest worker will eventually stall. On NYSL and attempted on LAG, we were deliberate on what we need to work on, with a solution focused approach. Forward planning with an action plan. Diagnostic.

There’s a lot more that he breaks it down, with focus and reflection, micro goal setting, compounding effect, teaching you how to think. Way too much to be writing on this journal.

The Moral of the Science: Potential Is Built, Not Found

Anders ends the book with a clear, almost moral conclusion:

Every human being is capable of far more than we assume.

The tragedy isn’t that most people fail to reach their potential — it’s that they never even learn how to approach it.

Schools, workplaces, and even sports systems are built around performance measurement, not practice design.

We reward outcomes, not processes.

We glorify talent, not adaptability.

Anders call is to reverse that — to create a culture that celebrates training design and continuous refinement as much as results.

That’s the real “road ahead.”

Reflection Prompts

- Where in my coaching or personal growth have I assumed a “ceiling” that’s really a design problem?

- How can I make improvement the core value of my environment, not performance?

- Who around me believes in talent myths — and how can I help them shift toward a design mindset?

- What system could I build that makes progress automatic — even on days when motivation is low?

- What does “rethinking potential” mean in the context of my field? How would that change how I teach, train, or lead?

Here’s the truth that Peak makes impossible to ignore:

You’re not born behind — you’re built behind.

And that means you can catch up.

Every skill gap is an information gap.

Every “talented” player is just someone who learned faster, got feedback sooner, and stayed deliberate longer.

You can build that.

Right now.

Through the system you design, the friction you embrace, and the feedback you demand.

Because improvement isn’t magic.

It’s math.

And if you put yourself at the edge — consistently, intentionally — your body and brain will adapt.

That’s what Anders proved in the lab, and what I’ve seen on the stage, in the ring, and in the game.

So stop saying “they’re built different.”

Start asking “how were they built?”

Then build yourself the same way.

If you want to begin your journey, I’d recommend the book here!

Let me know if you’d like to see more about topics in and around the journey and learning of leading a high-performance esports team. If you are interested, sign up here!

Follow me on Twitter @DREAL_JE and keep up to date with me in esports.

Follow me on Instagram for real-life content! @DREAL_JE

I host Viewer 8s and Sub 8s weekly, including tournaments with cash prizes! Make sure you join my discord and get involved! https://discord.gg/S9qRnxfkPy

Want Private Coaching to Dominate like a Pro from a World Champion? If so, book here https://dreal.co.uk/shop/coaching-session/